Our final destination of the day was Narrow Gauge Spring, which is on the backside of the Mammoth Terraces area. Apparently, there’s only one other place in the entire world – somewhere in China – that has exactly the same kind of conditions as this place.

The process of making this kind of formation requires rainwater, healthy microbe-supporting soil, limestone, and heat. It goes something like this: rainwater seeps down through the soil, where lots of healthy microbial activity uses up the oxygen in it and excretes plenty of extra carbon dioxide into it, making it more acidic. The water sinks into the ground and runs into the limestone, which is Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3). Calcium Carbonate doesn’t dissolve well in plain water at all, but there are two things that make it dissolve better: acid and heat. The heat from the magma under the park and the acidity of the water combine to dissolve a whole lot of the limestone. Then, somewhere, the heated water gets forced back up to the surface through a crack.

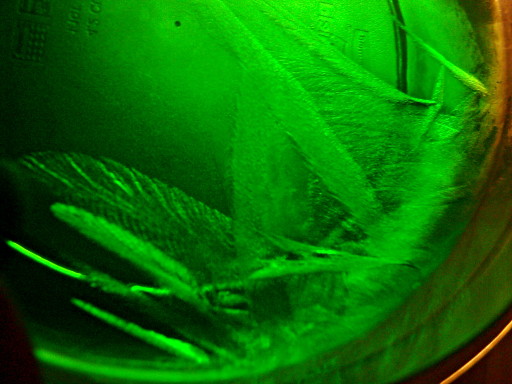

Where the water comes back in contact with the air, it can let off the extra carbon dioxide and heat. This doesn’t happen very fast in a deep pool, since this can only happen in a thin area near the top. Where the water overflows, though, it’s very shallow, and the carbon dioxide and heat can escape very quickly into the air. This makes the water suddenly become less acidic and less hot, and all that extra calcium carbonate can no longer stay dissolved. It crystallizes, making a hard calcium carbonate “shell” along the edge of the pool. The edge can end up growing some much over time that it forms an overhang with stalactite-like formations underneath it:

You can just make out an overhanging area in the upper-left of the photograph.

It was fun taking measurements of the water here. Water freshly removed from a pool initially showed up off the scale on our “Total Dissolved Solids” meters, but if you waited a few seconds the reading would drop down to where the meters could read it, and keep falling. Out of the pool, the water was cooling off quickly enough that the extra dissolved Calcium Carbonate was un-dissolving out of the water in tiny bits even as we stood there.

The water appeared to be about 56°C at the top of the pool where it was initially emerging. If you want an idea of not only that I am a nerd but what kind of nerd I am, I will mention that I think of this as “stewpot temperature”, and often wonder if there is any useful or tasty effects to be discovered in the microbial processes done by thermophilic microbes that live in these conditions. I’ll find out one of these days…

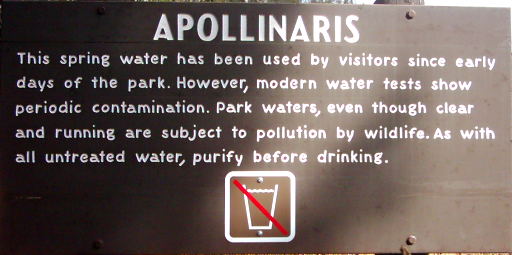

Oh, and a couple of bits of trivia about the Apollinaris Spring area from a couple of posts ago. Firstly, it was apparently named after a spring in Germany with the same name. Secondly, we briefly discussed the chemistry of carbon dioxide in water in class this week, and it turns out that the pH of 5.9 that Apollinaris Spring has is probably more basic than plain distilled water would be.

Now, anyone who’s had basic chemistry is probably a little baffled by this – after all, isn’t a pH of 7 that of pure water by definition? The answer is yes, but we’re not talking about pure water, we’re talking about water exposed to the air, where carbon dioxide can dissolve into the water. Working through the mathematics involved showed that distilled water should end up with a pH of about 5.6-5.7, at least at “standard temperature and pressure” (roughly sea-level air pressure and a temperature of around 72°F.). I have a suspicion as to why the Apollinaris Spring water seems less acidic than I might have expected, though.

They actually took our Apollinaris Spring water and ran it through an analytical instrument of some kind (I wasn’t there for it, but the description of the results made it sound like it was a “liquid chromatography” type of device). They found NO nitrates or nitrites in it. Since we’re talking about spring water percolating through healthy soil, I would have expected some nitrogen. I noticed, though, that although they checked for nitrite and nitrate, they didn’t check for reduced nitrogen – that is, ammonia.

I managed to score a tiny vial of the water during lab last Wednesday. When I get a chance to hit the pet store for some ammonia testing supplies, I’ll check that. If it’s there, it might explain the possibly slightly higher than expected pH. Similar to what happens to carbon dioxide and water, when ammonia (NH3) is dissolved into water(H2O), there tends to be some recombination of the atoms to make “ammonium hydroxide” (NH4OH), which is basic.

I don’t know if that’s what’s going on, but I intend to check.

There’s one more post worth of Field Trip stuff, and then I’ll be back onto other topics. Here’s a hint of what might come up, though: can anybody tell me what the effective pore size of pectin and cornstarch gels might be?…

Oh, right. Natural bottled-spring-water flavor. Hey, it’s natural, it’s got to be good for you, right?

Oh, right. Natural bottled-spring-water flavor. Hey, it’s natural, it’s got to be good for you, right?

My precious stock of expired JellO® is depleted by one more box, the packet ripped from its cardboard

My precious stock of expired JellO® is depleted by one more box, the packet ripped from its cardboard

“Now I lay me down to bed

“Now I lay me down to bed Expired JellO®! Deadly Poison, or Merely Debilitating? Can a human being withstand the toxic load of an *entire box* of it? Would he suffer embarassingly loud and messy gastrointestinal distress, or would immediate organ failure set in before this could take place? STAY TUNED TO FIND OUT!…

Expired JellO®! Deadly Poison, or Merely Debilitating? Can a human being withstand the toxic load of an *entire box* of it? Would he suffer embarassingly loud and messy gastrointestinal distress, or would immediate organ failure set in before this could take place? STAY TUNED TO FIND OUT!…

Last night, I plucked from the depths of my pantry an expired-2½-years-ago box of sugarless orange-flavored gelatin with which to begin this investigation. I blew the layer of dust off of the box, and carefully opened it, half-expecting to find some strange mutant gelatin-beast had developed in it over the years since expiration. One hand poised to protect myself should the creature leap from the box to eat my face in anger of being disturbed, I was both relieved and slightly disappointed to find nothing more than a foil packet containing what sounded like perfectly ordinary gelatin-powder. The packet proved to be intact, and the happy orange powder poured into a freshly-cleaned dish in a manner perfectly imitating that of wholesome non-expired gelatin. I dismissed the faint demonic snickering sound I seemed to hear as a figment of my fevered imagination and prepared the gelatin powder in the usual manner.

Last night, I plucked from the depths of my pantry an expired-2½-years-ago box of sugarless orange-flavored gelatin with which to begin this investigation. I blew the layer of dust off of the box, and carefully opened it, half-expecting to find some strange mutant gelatin-beast had developed in it over the years since expiration. One hand poised to protect myself should the creature leap from the box to eat my face in anger of being disturbed, I was both relieved and slightly disappointed to find nothing more than a foil packet containing what sounded like perfectly ordinary gelatin-powder. The packet proved to be intact, and the happy orange powder poured into a freshly-cleaned dish in a manner perfectly imitating that of wholesome non-expired gelatin. I dismissed the faint demonic snickering sound I seemed to hear as a figment of my fevered imagination and prepared the gelatin powder in the usual manner. I took up my electric kettle, containing distilled water, and threw the switch. Seconds passed into minutes. Minutes passed into more minutes. Then, the water began boiling vigorously, and I applied one cup (8 fluid ounces) of this to the dish of powder, stirring it with a tablespoon. It seemed to take at least two minutes of continuous stirring, but the deceptively innocent-looking powder finally dissolved without the slightest scent of brimstone. As prescribed by the instructions on the box, I added a further 8 fluid ounces of cold water (from the tap of my kitchen sink), stirred briefly to mix, and placed the dish in the refrigerator to gel overnight.

I took up my electric kettle, containing distilled water, and threw the switch. Seconds passed into minutes. Minutes passed into more minutes. Then, the water began boiling vigorously, and I applied one cup (8 fluid ounces) of this to the dish of powder, stirring it with a tablespoon. It seemed to take at least two minutes of continuous stirring, but the deceptively innocent-looking powder finally dissolved without the slightest scent of brimstone. As prescribed by the instructions on the box, I added a further 8 fluid ounces of cold water (from the tap of my kitchen sink), stirred briefly to mix, and placed the dish in the refrigerator to gel overnight. Day broke, and this very afternoon I took the now solidified mass from the refrigerator. This was it. My last chance to avoid whatever hellish abuses this disturbingly orange substance had planned for me. But no…it was far too late to turn back now. I took up my spoon, and devoured every last bit of happy orange jiggliness.

Day broke, and this very afternoon I took the now solidified mass from the refrigerator. This was it. My last chance to avoid whatever hellish abuses this disturbingly orange substance had planned for me. But no…it was far too late to turn back now. I took up my spoon, and devoured every last bit of happy orange jiggliness. I always find it interesting to go back and see the earlier stages of scientific endeavors – especially as relates to my own interests. There always seem to be things that have since been forgotten, abandoned, or glossed over in them.

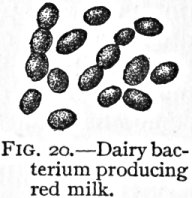

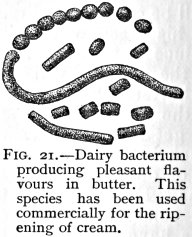

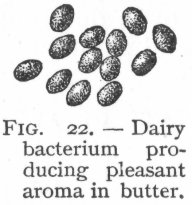

I always find it interesting to go back and see the earlier stages of scientific endeavors – especially as relates to my own interests. There always seem to be things that have since been forgotten, abandoned, or glossed over in them. H.W. Conn seems to have been most interested in dairy microbiology, so there is a substantial amount of space devoted to it. I’ve heard of “blue milk” before (Yummy!….Pseudomonas?), but not Red or Yellow milk. He also devotes space to discussing the affect of “good” (and “bad”) bacterial cultures on butter, cream, and cheeses. I’m not even sure if butter is cultured these days, or if they just churn it up fresh and cold with minimal growth. Dangit, one of these days we’re just going to have to move somewhere we can keep a miniature dairy cow so I can do some experimentation with real unpasteurized fresh milk.

H.W. Conn seems to have been most interested in dairy microbiology, so there is a substantial amount of space devoted to it. I’ve heard of “blue milk” before (Yummy!….Pseudomonas?), but not Red or Yellow milk. He also devotes space to discussing the affect of “good” (and “bad”) bacterial cultures on butter, cream, and cheeses. I’m not even sure if butter is cultured these days, or if they just churn it up fresh and cold with minimal growth. Dangit, one of these days we’re just going to have to move somewhere we can keep a miniature dairy cow so I can do some experimentation with real unpasteurized fresh milk. Bacterial phylogeny was so quaint back then. “Bacillus acidi lacti.” Ha! I love it. Interestingly, the term “Schizomycete” doesn’t appear anywhere in the text, though that may or may not be because it was considered unnecessarily technical for the intended audience. There’s actually very little about microbiological methods, too, which is the one major disappointment for me. Oh well, still interesting stuff. Conn actually mentions various “industrial” uses of bacteria including retting (soaking fibrous plants like flax or hemp so that bacteria eat the softer plant material to free the fibers), the roles of different bacterial cultures in curing tobacco, and even a fermentation in the production of opium (which Conn says is fungal rather than bacterial).

Bacterial phylogeny was so quaint back then. “Bacillus acidi lacti.” Ha! I love it. Interestingly, the term “Schizomycete” doesn’t appear anywhere in the text, though that may or may not be because it was considered unnecessarily technical for the intended audience. There’s actually very little about microbiological methods, too, which is the one major disappointment for me. Oh well, still interesting stuff. Conn actually mentions various “industrial” uses of bacteria including retting (soaking fibrous plants like flax or hemp so that bacteria eat the softer plant material to free the fibers), the roles of different bacterial cultures in curing tobacco, and even a fermentation in the production of opium (which Conn says is fungal rather than bacterial).

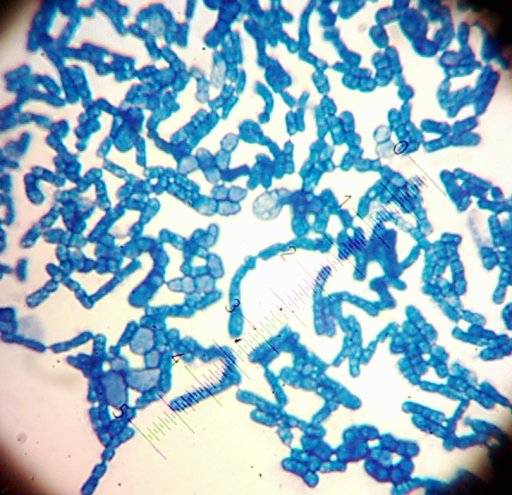

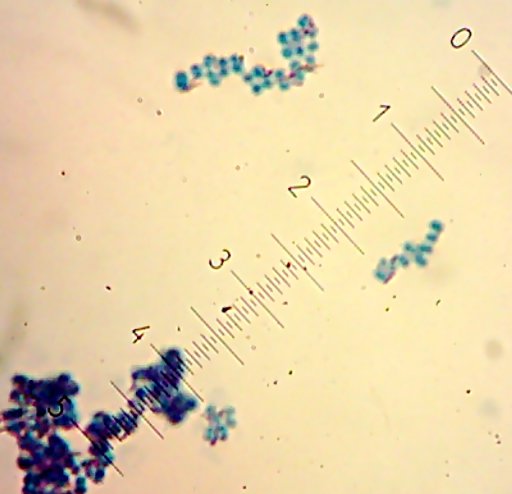

I also got two more Coccoid-Cluster-type Gram-positive bacterial isolates. The look pretty much the same under the microscope, though one had gooey wet, slightly larger colonies than the other’s smaller, hard-lump colonies. I see another one of those

I also got two more Coccoid-Cluster-type Gram-positive bacterial isolates. The look pretty much the same under the microscope, though one had gooey wet, slightly larger colonies than the other’s smaller, hard-lump colonies. I see another one of those