I can think of a number of things to complain about with regards to living where I do. However, it is nice that we live near enough to Yellowstone to day-trip there. In fact, it’s close enough for my local college to take field-trips there – which we did.

Environmental Chemistry spent the weekend there, examining the area, discussing the chemistry of the natural waters and geothermal features, and collecting samples (yes, we had a permit for this…).

We started with a stop by the side of the Madison River to collect a sample of the surface water. Clear, cool (12°C, or about 55°F), mildly basic (pH of about 8.0), and a TDS reading of about 300ppm, which is roughly the same as mildly to moderately hard tapwater, I suppose.

The sampling device -seen being hurled over the water here – is kind of interesting – it’s a hollow tube (a bit of plastic pipe) with two spring-loaded balls that slam shut on either end to trap the water inside when you tug on the string. That lets you throw the device out and trigger it when it gets to the precise spot that you want to take a sample from.

We made a brief stop at Beryl Spring afterwards. We didn’t do any sampling here, but we did talk about acid-sulfate water systems. “Reduced” sulfur – as Hydrogen Sulfide gas – comes boiling out from underground along with steam, and ends up being oxidized by oxygen from the air to become sulfate in the end – combining with the water and forming sulfuric acid.

Of course, it doesn’t go from sulfide to sulfate all at once. There’s a stop along the way as elemental sulfur. The whitish-yellow stuff here is crystals of elemental sulfur. The black stuff you see is…also crystals of elemental sulfur. The difference is just how the atoms of sulfur collect together. The black form is actually a little less stable than the yellow, so it tends to form first, but then slowly convert to the yellow form over time as the sulfur atoms settle into a more stable arrangement. Being a chemistry class, we didn’t really discuss the possible microbial activity that might be involved here. Note the small patch of dark-green there. I suppose this could be a “Green Sulfur Bacteria“, which does something like photosynthesis except that it makes sulfur instead of oxygen in the process. These are normally anaerobic but perhaps the concentration of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and carbon dioxide gas coming out of the ground right there is enough to crowd out the oxygen. Alternatively, it could just be a heat-loving cyanobacterium or something.

I really wish I wasn’t too poor to buy a good field microscope to go along with the good lab microscope that I am also too poor to buy…

The last two stops of the day – Appolinaris Spring and Narrow Gauge Spring – will be in the next post…

I always find it interesting to go back and see the earlier stages of scientific endeavors – especially as relates to my own interests. There always seem to be things that have since been forgotten, abandoned, or glossed over in them.

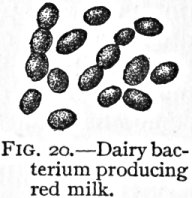

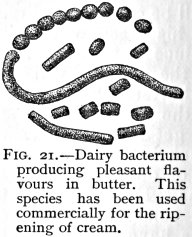

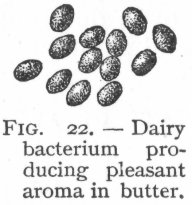

I always find it interesting to go back and see the earlier stages of scientific endeavors – especially as relates to my own interests. There always seem to be things that have since been forgotten, abandoned, or glossed over in them. H.W. Conn seems to have been most interested in dairy microbiology, so there is a substantial amount of space devoted to it. I’ve heard of “blue milk” before (Yummy!….Pseudomonas?), but not Red or Yellow milk. He also devotes space to discussing the affect of “good” (and “bad”) bacterial cultures on butter, cream, and cheeses. I’m not even sure if butter is cultured these days, or if they just churn it up fresh and cold with minimal growth. Dangit, one of these days we’re just going to have to move somewhere we can keep a miniature dairy cow so I can do some experimentation with real unpasteurized fresh milk.

H.W. Conn seems to have been most interested in dairy microbiology, so there is a substantial amount of space devoted to it. I’ve heard of “blue milk” before (Yummy!….Pseudomonas?), but not Red or Yellow milk. He also devotes space to discussing the affect of “good” (and “bad”) bacterial cultures on butter, cream, and cheeses. I’m not even sure if butter is cultured these days, or if they just churn it up fresh and cold with minimal growth. Dangit, one of these days we’re just going to have to move somewhere we can keep a miniature dairy cow so I can do some experimentation with real unpasteurized fresh milk. Bacterial phylogeny was so quaint back then. “Bacillus acidi lacti.” Ha! I love it. Interestingly, the term “Schizomycete” doesn’t appear anywhere in the text, though that may or may not be because it was considered unnecessarily technical for the intended audience. There’s actually very little about microbiological methods, too, which is the one major disappointment for me. Oh well, still interesting stuff. Conn actually mentions various “industrial” uses of bacteria including retting (soaking fibrous plants like flax or hemp so that bacteria eat the softer plant material to free the fibers), the roles of different bacterial cultures in curing tobacco, and even a fermentation in the production of opium (which Conn says is fungal rather than bacterial).

Bacterial phylogeny was so quaint back then. “Bacillus acidi lacti.” Ha! I love it. Interestingly, the term “Schizomycete” doesn’t appear anywhere in the text, though that may or may not be because it was considered unnecessarily technical for the intended audience. There’s actually very little about microbiological methods, too, which is the one major disappointment for me. Oh well, still interesting stuff. Conn actually mentions various “industrial” uses of bacteria including retting (soaking fibrous plants like flax or hemp so that bacteria eat the softer plant material to free the fibers), the roles of different bacterial cultures in curing tobacco, and even a fermentation in the production of opium (which Conn says is fungal rather than bacterial).

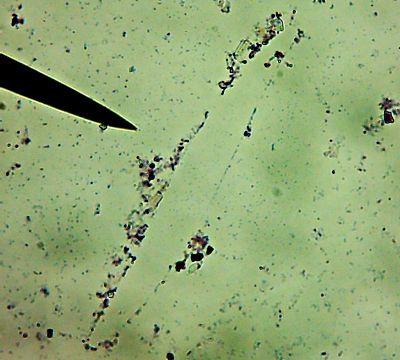

All right then, here, let me dry the sample out and heat fix it, then I’ll Gram Stain them for you.Wow. I guess soft, wet, squishy protozoal cell membranes don’t like being heat-fixed, do they? Ouch.

All right then, here, let me dry the sample out and heat fix it, then I’ll Gram Stain them for you.Wow. I guess soft, wet, squishy protozoal cell membranes don’t like being heat-fixed, do they? Ouch.

Okay, technically at least some of these things are diatoms rather than “protozoa“.

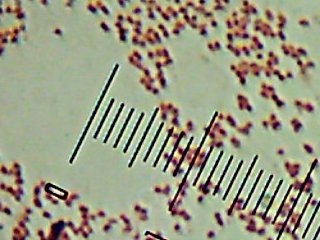

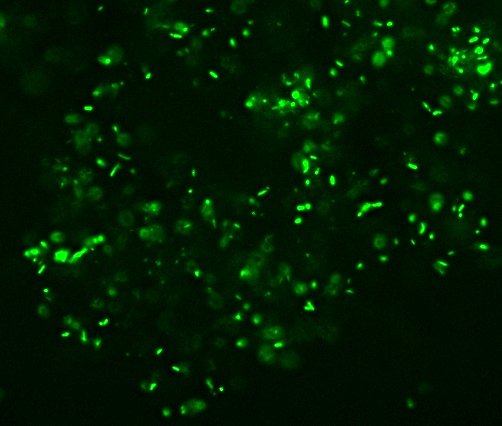

Okay, technically at least some of these things are diatoms rather than “protozoa“. Now, months later, I’m still not sure how much of the debris on those original slides was bacteria and how much was just crud from the samples. I did, however, get pictures of the 10 isolates that I wanted to try to identify (and of which, as you know from

Now, months later, I’m still not sure how much of the debris on those original slides was bacteria and how much was just crud from the samples. I did, however, get pictures of the 10 isolates that I wanted to try to identify (and of which, as you know from