Expired JellO®! Deadly Poison, or Merely Debilitating? Can a human being withstand the toxic load of an *entire box* of it? Would he suffer embarassingly loud and messy gastrointestinal distress, or would immediate organ failure set in before this could take place? STAY TUNED TO FIND OUT!…

Expired JellO®! Deadly Poison, or Merely Debilitating? Can a human being withstand the toxic load of an *entire box* of it? Would he suffer embarassingly loud and messy gastrointestinal distress, or would immediate organ failure set in before this could take place? STAY TUNED TO FIND OUT!…

Yes, loyal readers, as I type this I have subjected my own body to unthinkable risks to answer these very questions. That, dear readers, is how much I care about your health and welfare. You can thank me later…

…If I survive!

What does it mean to be an “Applied Empirical Naturalist”, anyway? As a naturalist, I look for natural explanations for natural observations. If I survive this ordeal, I will not explain it as being due to protection by supernatural forces, and conversely if I end up confined to an intensive care unit, my body ravaged by Expired-Gelatin-Syndrome, I will not seek to explain it as divine punishment for violating Kosher. As an Empirical naturalist, I investigate things by actual observation and direct testing wherever possible, rather than purely philosophical means. And – particularly important to me – Applied Empirical Naturalism is intended to convey that I am primarily interested in investigations with practical uses. Discovering the “Pineapple-Upside-Down Quark” with an umpty-brazillion-dollar particle accelerator and six months of supercomputer time to crunch the data wouldn’t do me, personally, much good. Knowing whether expired JellO® is safe to eat or not, however, has obvious practical application. Especially considering that I seem to have about 5 more boxes of the stuff in the pantry.

So, here I sit, perhaps writing my very last words ever before Expired-Gelatin-Shock causes my brains to swell up and explode messily and fatally from my ears like the popping of two superintelligent zits, in the service of Science. Here, then, is my story.

I begin by building my dire experiment around the following excessively-formal Valid Argument:

Upon expiration, JellO® becomes a deadly poison which causes great harm to those who dare ingest it

I prepare and consume an entire box of expired JellO®

Therefore, I suffer great harm due to its ingestion.

Last night, I plucked from the depths of my pantry an expired-2½-years-ago box of sugarless orange-flavored gelatin with which to begin this investigation. I blew the layer of dust off of the box, and carefully opened it, half-expecting to find some strange mutant gelatin-beast had developed in it over the years since expiration. One hand poised to protect myself should the creature leap from the box to eat my face in anger of being disturbed, I was both relieved and slightly disappointed to find nothing more than a foil packet containing what sounded like perfectly ordinary gelatin-powder. The packet proved to be intact, and the happy orange powder poured into a freshly-cleaned dish in a manner perfectly imitating that of wholesome non-expired gelatin. I dismissed the faint demonic snickering sound I seemed to hear as a figment of my fevered imagination and prepared the gelatin powder in the usual manner.

Last night, I plucked from the depths of my pantry an expired-2½-years-ago box of sugarless orange-flavored gelatin with which to begin this investigation. I blew the layer of dust off of the box, and carefully opened it, half-expecting to find some strange mutant gelatin-beast had developed in it over the years since expiration. One hand poised to protect myself should the creature leap from the box to eat my face in anger of being disturbed, I was both relieved and slightly disappointed to find nothing more than a foil packet containing what sounded like perfectly ordinary gelatin-powder. The packet proved to be intact, and the happy orange powder poured into a freshly-cleaned dish in a manner perfectly imitating that of wholesome non-expired gelatin. I dismissed the faint demonic snickering sound I seemed to hear as a figment of my fevered imagination and prepared the gelatin powder in the usual manner.

I took up my electric kettle, containing distilled water, and threw the switch. Seconds passed into minutes. Minutes passed into more minutes. Then, the water began boiling vigorously, and I applied one cup (8 fluid ounces) of this to the dish of powder, stirring it with a tablespoon. It seemed to take at least two minutes of continuous stirring, but the deceptively innocent-looking powder finally dissolved without the slightest scent of brimstone. As prescribed by the instructions on the box, I added a further 8 fluid ounces of cold water (from the tap of my kitchen sink), stirred briefly to mix, and placed the dish in the refrigerator to gel overnight.

I took up my electric kettle, containing distilled water, and threw the switch. Seconds passed into minutes. Minutes passed into more minutes. Then, the water began boiling vigorously, and I applied one cup (8 fluid ounces) of this to the dish of powder, stirring it with a tablespoon. It seemed to take at least two minutes of continuous stirring, but the deceptively innocent-looking powder finally dissolved without the slightest scent of brimstone. As prescribed by the instructions on the box, I added a further 8 fluid ounces of cold water (from the tap of my kitchen sink), stirred briefly to mix, and placed the dish in the refrigerator to gel overnight.

I lay awake in bed for hours, wondering if I was doing the right thing. Was I insane? Did I not remember the tales of Jeckyll and Hyde? Of Doctor Frankenstein? Of Pons and Fleischman? What horrible fate was I setting myself up for? Finally, I dropped into a fitful slumber, disturbed only by dreams of amorphous orange demons stalking me to feast upon my soul…

Day broke, and this very afternoon I took the now solidified mass from the refrigerator. This was it. My last chance to avoid whatever hellish abuses this disturbingly orange substance had planned for me. But no…it was far too late to turn back now. I took up my spoon, and devoured every last bit of happy orange jiggliness.

Day broke, and this very afternoon I took the now solidified mass from the refrigerator. This was it. My last chance to avoid whatever hellish abuses this disturbingly orange substance had planned for me. But no…it was far too late to turn back now. I took up my spoon, and devoured every last bit of happy orange jiggliness.

This was approximately seven hours ago. In the intervening time, I have experienced the following symptoms: Occasional thirst, mild generalized anxiety about the near future, hunger, and an urge to write this blog post in a hyperbolic language more suited to an H.P. Lovecraft story than a scientific report. In other words…I appear to have been entirely unaffected, despite consuming an entire box of expired gelatin.

I’ve been taught that when hypothesis-testing, one considers the “null hypothesis”. That is, the hypothesis that would falsify the one that I’m starting with. In this case, it would be something to the effect of “I will suffer no harm whatsoever from eating expired JellO®”. Given the results in this experiment I must – in the tortured language of philosophical science – “fail to reject the null hypothesis”, because my results show no evidence whatsoever that I have suffered harm from eating expired gelatin. In other words, I cannot rationally cling to my original hypothesis as written, and must confess that perhaps expired instant gelatin still in intact packaging may, in fact, be harmless.

Ah, but I know what happens now. “Cad!”, you cry! “Fraud! Sham! This experiment is, like, totally bogus! This is not normal JellO® but a sugar-free impostor! And furthermore, this isn’t even JellO®-brand gelatin, but a cheap knock-off brand! How dare you, sir, feed us this crap, which proves nothing!”

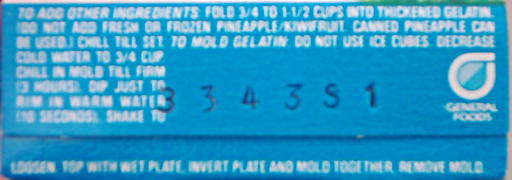

I answer in two parts: Firstly, ladies and gentlemen who are my readers, I assure you that the contents of the less-famous brand and the official Kraft® Foods brand are essentially identical, and indeed, might conceivably have come from the same source. It’s common practice for one factory’s product to be shipped to multiple sellers who each offer it under their own label, as the wide variety of affected brands during the recent “salmonella peanut butter” scare demonstrated. And secondly: as it happens, I also have in my possession a box of JellO®-brand lime-flavored gelatin, WITH sugar, which although it lists no obvious “expiration date”, has a code stamped on the box indicating that it was originally packaged in late 2003, and therefore should have exceeded the expected 24-month shelf-life about the same time as today’s test subject did. I swear to you, dear readers, that I will repeat my experiment with this sample next.

Stay tuned: “Expired JellO II: Lime’s Revenge”, coming soon to a blog near you!

UPDATE: The Expired JellO® Saga continues here!

One of my projects is to appease one of my weaknesses. As I’ve probably mentioned before, “Gluttony” is my second-most-favorite deadly sin. If you’ve been listening to “Stir-Fried Random” (new episode coming shortly, I promise) and reading the blog recently, you can probably tell that among my large collection of “a peculiar fondess for [whatever]” attributes that I possess is one for “Cinnamon Bears“. While they’re not too bad as far as candy goes, they’re still not good for me. Plus, like any candy they can get to be kind of expensive. (Dear Amazon.com: The package plainly says “2/$100“. You’re selling these in groups of 12. Now, I only carried my calculation out to 3 significant figures, but I estimate that this should cost $6.00. Not “$6.85”. Plus $7.90 for shipping. $14.75 for $6.00 worth of convenience-store candy is just stupid.)

One of my projects is to appease one of my weaknesses. As I’ve probably mentioned before, “Gluttony” is my second-most-favorite deadly sin. If you’ve been listening to “Stir-Fried Random” (new episode coming shortly, I promise) and reading the blog recently, you can probably tell that among my large collection of “a peculiar fondess for [whatever]” attributes that I possess is one for “Cinnamon Bears“. While they’re not too bad as far as candy goes, they’re still not good for me. Plus, like any candy they can get to be kind of expensive. (Dear Amazon.com: The package plainly says “2/$100“. You’re selling these in groups of 12. Now, I only carried my calculation out to 3 significant figures, but I estimate that this should cost $6.00. Not “$6.85”. Plus $7.90 for shipping. $14.75 for $6.00 worth of convenience-store candy is just stupid.) The trick is going to be getting the right texture. I’ve found recipes online that use gelatin or pectin. The store-bought product, though, uses “Modified Food Starch”. How exactly do they “modify” the food starch? I vaguely recalled that it was an acid-treatment process that partially breaks up the long glucose polymers, but I wasn’t sure. As any modern nerd would do, I decided to ask My Friend, The Internet.

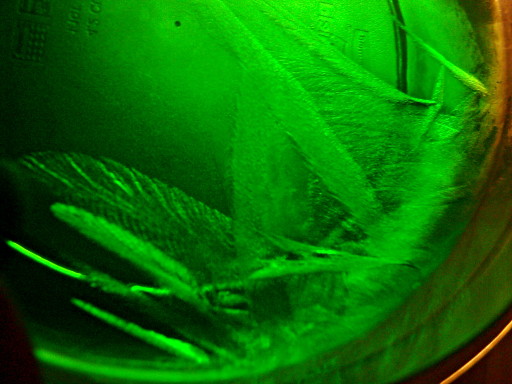

The trick is going to be getting the right texture. I’ve found recipes online that use gelatin or pectin. The store-bought product, though, uses “Modified Food Starch”. How exactly do they “modify” the food starch? I vaguely recalled that it was an acid-treatment process that partially breaks up the long glucose polymers, but I wasn’t sure. As any modern nerd would do, I decided to ask My Friend, The Internet. Julius Robert Petri’s idea was so useful that we still use it today. Oh, yeah, and they named the

Julius Robert Petri’s idea was so useful that we still use it today. Oh, yeah, and they named the

My precious stock of expired JellO® is depleted by one more box, the packet ripped from its cardboard

My precious stock of expired JellO® is depleted by one more box, the packet ripped from its cardboard

“Now I lay me down to bed

“Now I lay me down to bed Expired JellO®! Deadly Poison, or Merely Debilitating? Can a human being withstand the toxic load of an *entire box* of it? Would he suffer embarassingly loud and messy gastrointestinal distress, or would immediate organ failure set in before this could take place? STAY TUNED TO FIND OUT!…

Expired JellO®! Deadly Poison, or Merely Debilitating? Can a human being withstand the toxic load of an *entire box* of it? Would he suffer embarassingly loud and messy gastrointestinal distress, or would immediate organ failure set in before this could take place? STAY TUNED TO FIND OUT!…

Last night, I plucked from the depths of my pantry an expired-2½-years-ago box of sugarless orange-flavored gelatin with which to begin this investigation. I blew the layer of dust off of the box, and carefully opened it, half-expecting to find some strange mutant gelatin-beast had developed in it over the years since expiration. One hand poised to protect myself should the creature leap from the box to eat my face in anger of being disturbed, I was both relieved and slightly disappointed to find nothing more than a foil packet containing what sounded like perfectly ordinary gelatin-powder. The packet proved to be intact, and the happy orange powder poured into a freshly-cleaned dish in a manner perfectly imitating that of wholesome non-expired gelatin. I dismissed the faint demonic snickering sound I seemed to hear as a figment of my fevered imagination and prepared the gelatin powder in the usual manner.

Last night, I plucked from the depths of my pantry an expired-2½-years-ago box of sugarless orange-flavored gelatin with which to begin this investigation. I blew the layer of dust off of the box, and carefully opened it, half-expecting to find some strange mutant gelatin-beast had developed in it over the years since expiration. One hand poised to protect myself should the creature leap from the box to eat my face in anger of being disturbed, I was both relieved and slightly disappointed to find nothing more than a foil packet containing what sounded like perfectly ordinary gelatin-powder. The packet proved to be intact, and the happy orange powder poured into a freshly-cleaned dish in a manner perfectly imitating that of wholesome non-expired gelatin. I dismissed the faint demonic snickering sound I seemed to hear as a figment of my fevered imagination and prepared the gelatin powder in the usual manner. I took up my electric kettle, containing distilled water, and threw the switch. Seconds passed into minutes. Minutes passed into more minutes. Then, the water began boiling vigorously, and I applied one cup (8 fluid ounces) of this to the dish of powder, stirring it with a tablespoon. It seemed to take at least two minutes of continuous stirring, but the deceptively innocent-looking powder finally dissolved without the slightest scent of brimstone. As prescribed by the instructions on the box, I added a further 8 fluid ounces of cold water (from the tap of my kitchen sink), stirred briefly to mix, and placed the dish in the refrigerator to gel overnight.

I took up my electric kettle, containing distilled water, and threw the switch. Seconds passed into minutes. Minutes passed into more minutes. Then, the water began boiling vigorously, and I applied one cup (8 fluid ounces) of this to the dish of powder, stirring it with a tablespoon. It seemed to take at least two minutes of continuous stirring, but the deceptively innocent-looking powder finally dissolved without the slightest scent of brimstone. As prescribed by the instructions on the box, I added a further 8 fluid ounces of cold water (from the tap of my kitchen sink), stirred briefly to mix, and placed the dish in the refrigerator to gel overnight. Day broke, and this very afternoon I took the now solidified mass from the refrigerator. This was it. My last chance to avoid whatever hellish abuses this disturbingly orange substance had planned for me. But no…it was far too late to turn back now. I took up my spoon, and devoured every last bit of happy orange jiggliness.

Day broke, and this very afternoon I took the now solidified mass from the refrigerator. This was it. My last chance to avoid whatever hellish abuses this disturbingly orange substance had planned for me. But no…it was far too late to turn back now. I took up my spoon, and devoured every last bit of happy orange jiggliness.